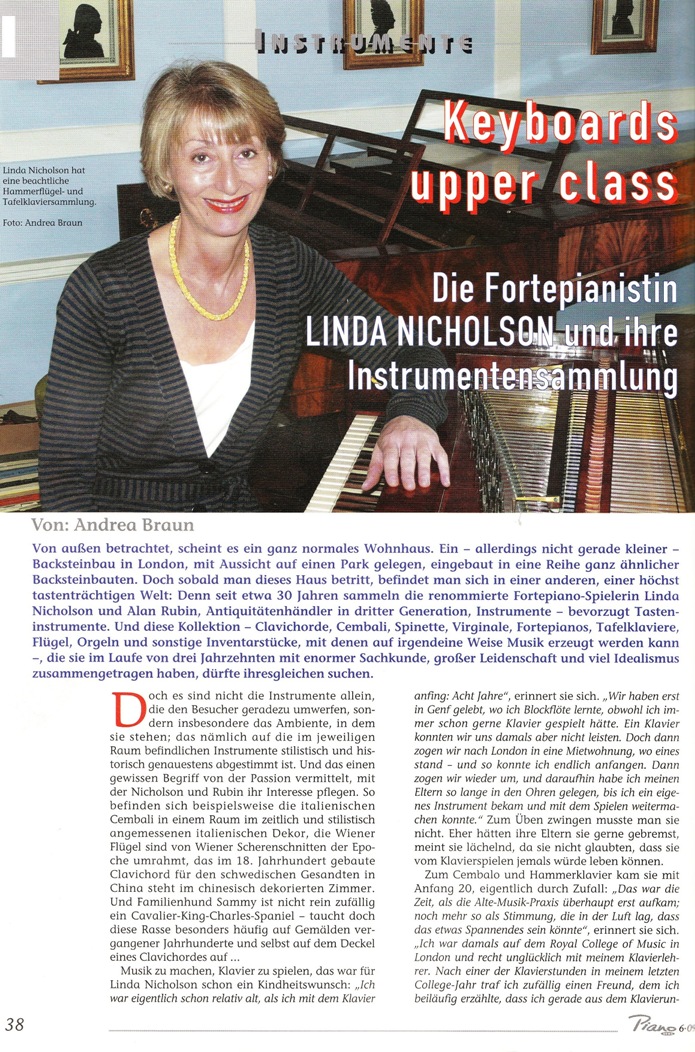

PIANO NEWS November/December 2009 The fortepianist Linda Nicholson and her instrument collection By Andrea Braun Viewed from the outside, it seems to be quite a normal home. A brick building in London– albeit not exactly small, overlooking a park, one of a row of similar brick buildings. However as soon as one enters this house, one finds oneself in another, highly keyboard orientated, world: for Linda Nicholson, the well-known fortepianist, and her husband, a third-generation antique dealer, have been collecting instruments for about thirty years, predominantly keyboard instruments. And this collection–clavichords, harpsichords, spinets, virginals, fortepianos, square pianos, organs and other items on which music can be produced in some way– was put together in the course of three decades with enormous knowledge, great passion and much idealism. However it is not just the instruments that strike the visitor, but altogether the ambience in which they stand: the fact that in each respective room the instruments are most precisely matched historically and stylistically. And that conveys an idea of the passion with which Nicholson and her husband cultivate their interest. So, for example, the Italian harpsichords are in a room with an Italian decor of the appropriate style and date, the Viennese pianos are surrounded by Viennese silhouettes of the period, and the 18th century clavichord possibly made for the Swedish envoy to China stands in a room decorated in the Chinese style. And it is not by chance that the family's dog, Sammy, is a Cavalier King Charles spaniel– this breed often appears in paintings of previous centuries and even on the lid of a clavichord.... To make music, to play the piano, was already a wish for Linda Nicholson as a child. "I was actually already relatively old when I started to play the piano: in fact eight years", she remembers. "We were living in Geneva, where I learnt the recorder. I would have liked to learn the piano, but at that time we couldn't afford one. However, we then moved to London and lived in rented accommodation, where there was a piano, and so I could start at last. Then we moved once more, and I pestered my parents until I got an instrument and could continue learning." She didn't need to be made to practise. Her parents rather tried to hold her back, she says smilingly, as they didn't think she would ever be able to make a living from playing the piano. It was more or less by chance that she began the harpsichord and fortepiano at the age of twenty. "At that time the early music movement was just getting going: there was a feeling in the air that something exciting could be happening", she remembers. "I was at the Royal College of Music and was really unhappy with my piano teacher. After one of my piano lessons in my last year I bumped into a friend to whom I said I found my piano lessons unsatisfactory, that I didn't really want to continue with them, and that what I really wanted was to learn the harpsichord instead. To which he said:'Well, do it then! Change to the harpsichord!'" The young pianist did precisely that–and found in Ruth Dyson a teacher who brought her closer to the instrument and its literature. "In addition was the coincidence that I met someone whom I would later marry. He had already started collecting instruments, just a couple at that stage, but still it was a start", Nicholson relates. So one thing led to another and to her great interest in historical instruments, especially the fortepiano, as she was particularly drawn to the repertoire written for this instrument. "The impetus for the collection came from the combination of my husband being a passionate collector and antique dealer, and I a pianist. But gradually I also realised that I was learning an unbelievable amount about the music through these instruments, and that I was very privileged to have the opportunity of playing them: an opportunity that hardly any pianist has!" An opportunity that she understood how to use. In 1978 she won the first prize at the Concours International du Pianoforte in Paris, the first of its kind to be held. And in 1983 the second prize (the first was not awarded) at the famous competition "Musica Antiqua" in Bruges, where she also won the audience prize. Since then she has appeared on many important concert platforms, and has made many recordings: with her ensemble, The London Fortepiano Trio; Scarlatti sonatas on the fortepiano, but also Mozart sonatas and Beethoven Bagatelles; and currently the complete sonatas for violin and piano by Beethoven, with the baroque violinist, Hiro Kurosaki. Needless to say all of these were on original instruments, mostly her own, for she does not keep these as museum pieces for quiet contemplation, but travels with them throughout Europe. It isn't a life in a museum that Nicholson leads in her London home, but a kind of constant interchange between these audible witnesses of a distant past. "What really fascinates me about these historical instruments, is the variety. We have instruments from 1572 to 1831 in our collection. And then there are all the different types of instruments, and even within each type there is an enormous variety of sounds and colours. For example, we have six Viennese fortepianos, ranging from 1797 to 1831, and through these one can see a clear development. Which doesn't mean that one must play a Beethoven sonata of 1797 on an instrument of 1797–that isn't the point. What matters far more, is that one can play each instrument in a different manner. If the depth of the keys is very shallow and the touch is very light, one can play fast passages very fast. But maybe the tone does not last so long. That can dictate the tempo of a piece. And then the balance. I have two pianos of 1797, one by Anton Walter, who was Mozart and Beethoven's favourite maker, and another by Johann Schantz, whom Haydn favoured. These two instruments, from the same date, have completely different characters. Whereas the sound of the Walter is warm and singing– and I think it is no coincidence that Mozart prized this so much– the Schantz is brighter, more brilliant and louder, suiting Haydn's more short-breathed and 'broken' compositional style. Even if one plays two instruments by Walter from the same time, there can be a big difference between the balance of treble to bass. If one plays one piece on two different instruments one must go about it in a quite different way, because perhaps one piano cannot match the dynamic range of the other– so one must play everything quieter. One has to follow what the instrument demands". Nicholson no longer plays the modern piano. "Many people play wonderfully on it, but it's not really what I want. If for example one plays Bach on it, then I don't think one can really come close to what Bach imagined. On the other hand, there are fine musicians, such as Glenn Gould, who make something quite new out of it. However for me it is like the arrangements of Bach by Ferrucio Busoni: new compositions, which can be very beautiful but I don't think that one can learn what Bach hoped to express in his music from those. The same applies to Mozart on the modern piano. Again, there are fine players who do remarkable things, but really one is trying to do something contrary to the music. The scale on which these works were written–the lengths of the phrases, of the movements, of the pieces– are all related to an instrument which has half of the power of a modern piano. If one tries to reproduce this scale on the modern piano, then one cannot use the possibilities of the instrument. I'm not sure whether it's possible to do justice to both the music and the instrument in this case." A tour through the house clarifies what she means as she plays an appropriate piece on each restored instrument. And then one experiences some surprises, particularly with regard to tempi and phrasings of well-known pieces! (Shortened version of article) |